El Museo del Barrio is pleased to present Nexus New York: Latin/American Artists in the Modern Metropolis, the inaugural exhibition in its newly renovated and expanded facilities. The exhibition coincides with El Museo’s public reopening as well as the launch of El Museo’s 40th Anniversary festivities, which will continue all year.

Nexus New York: Latin/American Artists in the Modern Metropolis explores the interactions between Caribbean and Latin American artists and U.S.-born and European artists working in New York in the early twentieth century, who together fomented many of that era’s most important avant-garde art movements. Nexus New York is the first exhibition to explore the profound way these artistic exchanges between Latino and non-Latino artists deeply impacted art and art movements in this city and throughout the world for years to come. The exhibition is also representative of El Museo’s mission to produce programming and new scholarship on the significant yet sometimes overlooked contributions made by Latino, Caribbean, and Latin American artists.

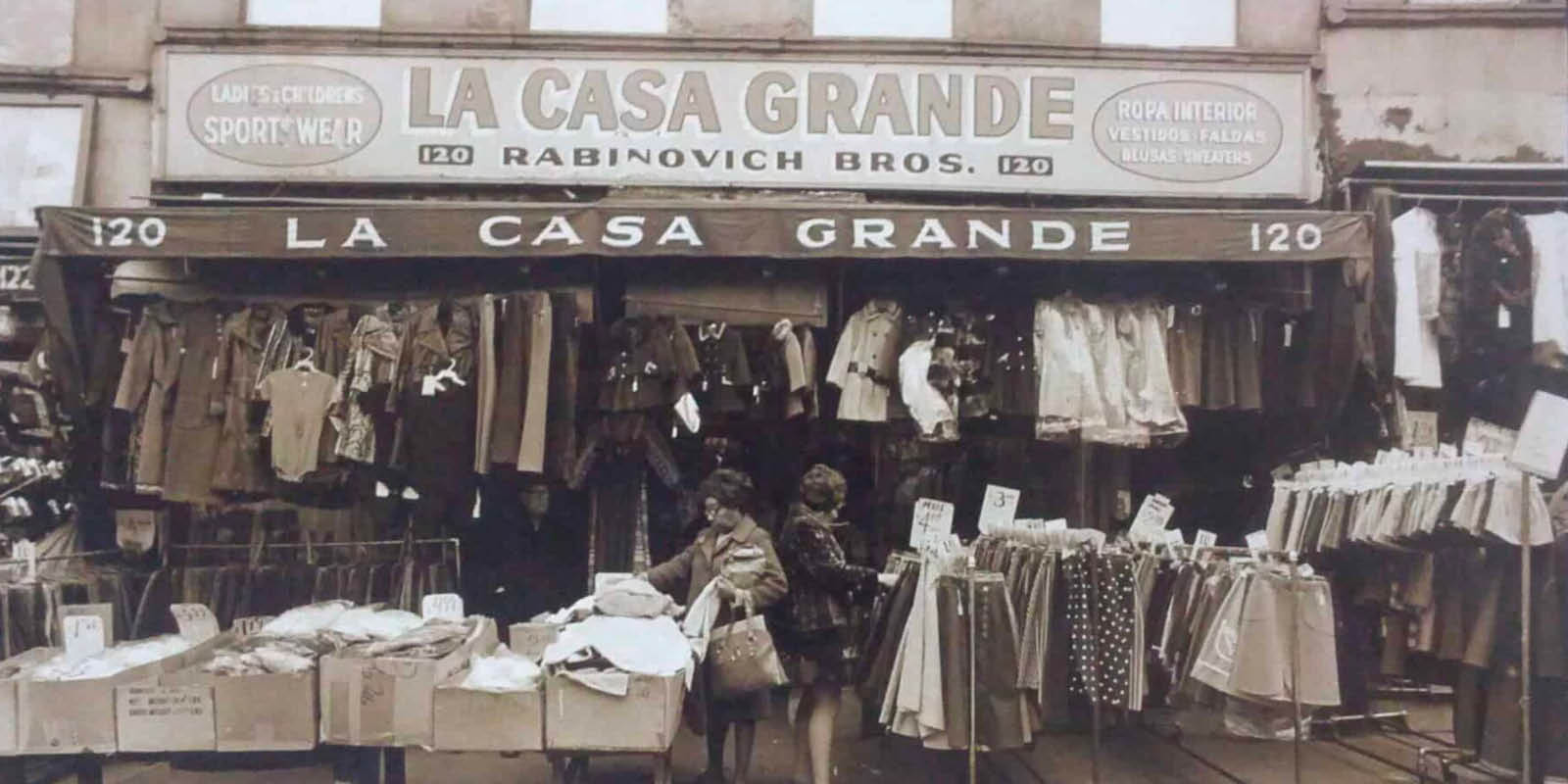

This ambitious exhibition will present for the first time together more than 200 important works by artists from Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru, Puerto Rico, Uruguay, as well as U.S. and European artists working in New York. Contextual material—such as period photographs, original magazines and books, reproductions of poems, writing, and other documentary materials— will also be on display to elucidate and bring to life the nature of these historical, collaborative, and experimental environments.

A lavishly illustrated, bilingual scholarly catalogue, distributed by Yale University Press will accompany the exhibition with essays that focus on specific environments, exchanges, or centers, and which detail the various artists’ New York milieus and artistic development. Nexus New York is currently supported by The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Trust, MetLife Foundation, The Terra Foundation for American Art, Agnes Gund, The Henry Luce Foundation, Bacardi and the Dedalus Foundation.

Nexus New York will be presented simultaneously with Voces y Visiones: Four Decades through El Museo del Barrio’s Permanent Collection, made possible thanks to the generous support of American Express. The Voces y Visiones exhibition will mark the debut of the Carmen Ana Unanue Galleries, El Museo’s first-ever galleries dedicated to highlights from its permanent holdings. The Permanent Collection Galleries will serve to present one of the oldest and most important collections of twentieth-century Caribbean, Latino, and Latin American art in the U.S. The Collection also highlights the Museum’s New York centered collecting, exhibiting, and institutional focus, which differentiates it from other selective or encyclopedic museum collections of Latin American art in the United States.

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

Through both chronological and simultaneous groupings that focus on sites of artistic contact, visitors will explore diverse locations around New York, emphasizing the institutions, schools, and groups that galvanized the cosmopolitan activity in which Caribbean and Latin American artists played key roles. Proceeding somewhat chronologically through El Museo’s newly renovated space, the first section of Nexus New York will focus on artists who chose realist or expressionist formal means during a period from approximately 1910 through the 1920s, and their key artistic exchanges as they traveled to New York and its environs to study with renowned American teachers.

One locus of such exchanges was The Art Students League of New York, a venerable site welcoming foreign students to work and study since 1875. Hailing from Puerto Rico, artist Miguel Pou y Becerra traveled to New York in 1919 to study at the Art Students League with Robert Henri, whose realist Ashcan School theories paralleled Pou’s own developing proposition to document quotidian life on his island in order to venerate its national ideals. Similarly, Celeste Woss y Gil left the Dominican Republic to study at the League from 1922 to 1924 and 1928 to 1931. Previously stifled by her island’s conservative artistic environment, she embraced teachers such as George Luks and his fleshy, gritty painted realities. Upon her return to Santo Domingo, her bold nude mulatto and black females established her as an influential teacher to younger Dominican generations, later going on to direct an important art academy that initiated the founding of the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes in 1942. Other educational interactions profiled in this section will include that of Anita Malfatti, who journeyed from Brazil to study at the Independent School of Art with influential teacher Homer Boss. After working alongside progressive American-based colleagues from 1915 to 1916, she returned to Brazil where her solo 1917 exhibition utilized a groundbreaking expressionist language, setting an important precedent for her country, the key 1922 celebration of São Paulo’s “Modern Art Week”, and the course of modern Brazilian art.

A more complex exchange was that of Alice Neel and Carlos Enríquez who met in 1924 at the Pennsylvania Academy summer school. They were married in 1925 and returned to his home in Havana, Cuba, where Enríquez participated in the early vanguard exhibitions. After returning to New York in 1927, they eventually separated, however the impact of the Caribbean modern movement on Neel’s work continued to evidence itself in her bold formal style and social agenda. In addition to many early works, their haunting portraits of their daughter Isabetta are brought together for the first time. Working as a WPA artist in 1935, Neel met the Puerto Rican musician and entertainer José Negrón, moving with him a few years later to El Barrio, where El Museo is based today. Although they parted ways in 1939, Neel continued to live in El Barrio for the following 26 years, often painting the people and places of the neighborhood. Neel’s early embrace of the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, as well as her initial exposure to the vanguardia and the social ideals of the Cuban modernist movement, facilitated her comfort in El Barrio, which she adopted as her home.

The second section will include pioneering travelers to New York who moved within Dada and Cubist circles in the 1900s and 1910s. This section will, in particular, focus on the 291 Gallery, the De Zayas Gallery, and the Modern Gallery. The collaboration between the artists Alfred Stieglitz and Marius de Zayas was instrumental in bringing European avant-garde art to the United States and helped to foster an American avant-garde tradition. While Stieglitz’s role in this movement is well acknowledged, less attention has been paid to the integral role de Zayas played as an artist, gallerist, and writer.

De Zayas served as an important catalyst in Dada circles. After relocating to New York City in 1907, the artist quickly found employment and gained notoriety as a caricaturist for New York’s The Evening World. The attention de Zayas garnered from these caricatures also drew the attention of Alfred Stieglitz, the infamous photographer who ran the progressive Little Gallery of the Photo-Secession or “291” as it was more often called. In 1909, Stieglitz gave de Zayas his first show in New York, comprised of charcoal caricatures and went on to exhibit de Zayas’s work three times between 1909 and 1913. De Zayas’ relationship with 291 united the circle of avantgarde artists and intellectuals—from both sides of the Atlantic—who influenced the New York art scene. During a 1910-1911 trip to Europe, he helped organize the first exhibition of Picasso’s work in the United States for 291.

De Zayas became close friends with the French-Cuban artist Francis Picabia who visited New York extensively between 1913 and 1915. De Zayas opened The Modern Gallery, a somewhat more commercial venture, to serve the 291 circle, and eventually gained enough financial support to begin publishing the journal, 291. De Zayas maintained strong connections to his European friends throughout this time, particularly Picabia. Their relationship was influential for both artists’ careers and several scholars have discussed the significance of de Zayas’s abstract, algebra-based portraits for Picabia’s mechanamorphic “object-portraits”, which the artist began during his stay in New York in the summer of 1915. Their artistic dialogue will be explored through 15 examples of the 291 and 391 journals, which will be featured in this section.

The third section will feature Joaquin Torres-Garcia whose time in New York from 1920 to 1922 fostered his radical formal experimentation and influenced others. The Uruguayan innovator travelled to the city to manufacture wooden toys of his own design. Supported by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, Juliana Force, Katherine Dreier, the Anderson Gallery and others in New York, Torres-García met Marcel Duchamp, Joseph Stella, Max Weber and the Peruvian Carlos Baca-Flor, among others. In 1921, the Whitney Studio Club, which had been founded by Vanderbilt Whitney and later expanded to become the Whitney Museum of American Art, honored Torres-García with an exhibition in collaboration with Stuart Davis, who was also developing a graphic, iconic abstracted pictorial language. Torres-García was similarly interested in popular signage and cartoons and the language of the modern street. The praising reviews of his early work in New York, as well as works themselves which were collected and exhibited by A. E. Gallatin’s Gallery of Living Art in Washington Square, had a decisive impact on many subsequent American artists long after the Uruguayan returned to Montevideo, including the well-documented example of Adolph Gottlieb. Works by Torres-Garcia, Davis, Stella and Gottlieb will explore their urban abstractions, while numerous sketchbook pages, manuscript collages, and a never-before-seen film will offer a glimpse into Torres-Garcia’s experience of New York in the 1920s.

The fourth section will look at the expansive influence of the Mexican modernists in New York, whose dominance had been felt beginning in the 1920s, but which peaked during the 1930s. One important location was Union Square, where both the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop and the New School for Social Research were located. In 1936, Mexican artist David Alfaro Siqueiros founded his “Experimental Workshop (A Laboratory of Modern Techniques in Art)” in Union Square, the primary goal of which was to develop, promote and teach experimental techniques that would lead to the crystallization of a truly revolutionary art form.

For Siqueiros, the future of mural painting was dependent upon finding a new way to communicate a message of revolution to the masses without employing what he thought of as the “primitivist” leanings of other muralists of the time, such as Diego Rivera. Upon Siqueiros’s arrival as an official Mexican delegate to the American Artists Congress, American artists such as Harold Lehman, Jackson Pollock and his brother Sandy McCoy, the Bolivian Roberto Berdecio, the Mexicans Luis Arenal, Antonio Pujol and José Gutiérrez, and others, eagerly joined his call to create a laboratory-like environment that fostered collaborative artistic and political experimentation. The overarching goal of the workshop was to utilize the tools of modern industry to create a style appropriate to Siqueiros’ communist ideologies. Artists explored, side-by-side with the master muralist, what Siqueiros called “controlled accidents”, reliant upon new materials such as nitrocellulose pigments, photography and even film. The use of spray guns, stenciling, hurling, dripping, and splattering were all employed in this new form of art making, the implementation of which left an indelible and significant mark on the most infamous workshop participant, the young Jackson Pollock.

While the workshop had a short lifespan (Siqueiros departed to fight in the Spanish Civil War in 1937), its impact on the trajectory of modern art in the United States, Mexico and beyond is undeniable. Paintings and works on paper by Siqueiros, Pollock, Arenal, Lehman and others, along with documentation of their collaborative workshop projects, and workshop-inspired activities, particularly a now lost mural cycle by Roberto Berdecio, will present their experimental and political aims and achievements.

The exhibit will also feature for the first time ever, a fresco panel from Diego Rivera’s New Workers’ School Cycle, completed in late 1933 after his ill-fated Rockefeller Center mural, one of the most significant art world controversies ever to take place on U.S. soil. This scandal involved Rivera’s 1933 mural Man at the Crossroads, which was destroyed in 1934 before completion due to Rivera’s sympathetic depiction of Lenin. Frustrated Rivera utilized his large Rockefeller family fee to carry out the Union Square mural cycle that clearly depicted his political ideologies, once the other project was abruptly destroyed.

Before this controversy, Rivera, who spent 1930 to 1934 in the United States, was honored with a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1931. While he worked on the Rockefeller mural, many artists, including Charles Alston, visited him. Alston was an influential artist and teacher in Harlem, serving at the Harlem Community Arts Center, a project of the WPA. The influence of Rivera can clearly be seen in Alston’s 1936 murals at Harlem Hospital, the drawings of which will be featured. The Harlem arts community’s interest in the Mexican model can be appreciated both artistically and politically.

This section will also examine the connection between the goals of the Mexicanidad movement and that of the “New Negro” project, based in Harlem. Pioneers include Miguel Covarrubias, who moved to New York in 1923, publishing his artworks and impressions of the city in Vanity Fair and The New Yorker. José Clemente Orozco also spent considerable time in New York, from 1927 to 1934. Following his compatriot Covarrubias, he was also interested in urban issues, and several of his scenes of the city will be featured in Nexus New York. Other artists featured in this section include Jean Charlot, Orozco’s close friend. A French-born artist who relocated to Mexico in 1922, Charlot played a pivotal role in the development and promotion of modern Mexican art.

The fifth section will focus on various sites of Surrealism, which gained currency as international artists joined forces in New York starting with World War II’s approach in the late 1930s to the war’s end. These include the 1939 World’s Fair and the New School for Social Research, which housed Paris’ Atelier 17 during the War. The “World of Tomorrow” World Fair attracted over 44 million visitors to its spectacular events and National Pavilions, including Salvador Dalí’s notorious “Dream of Venus” exhibition. Ecuadorians had a strong presence as well with a mural painted by Camilo Egas with the assistance of his compatriot, Eduardo Kingman. Egas, who arrived in New York in 1927, directed the New School’s art workshops from 1935 to 1962 throughout many years of international crossover, and was an instrumental figure in fomenting a mix of social realist and avant-garde personalities.

Candido Portinari of Brazil, who had garnered attention at the 1935 Carnegie International, also sent major panels to the 1939 World’s Fair, although he did not finally visit the city until late 1940 for his retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art when he also undertook a series of murals for the Library of Congress. Frida Kahlo, who had spent 1930 to1934 in the United States with her husband, Diego Rivera, returned in 1938 for a solo exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery as she was on her way to Paris to exhibit with André Breton.

Most Surrealist circles in New York, however, centered on The New School for Social Research. This university, which had also commissioned frescos from Orozco in 1930- 1931, and Camilo Egas in 1932, was a progressive base for many European artists fleeing both the Spanish Civil War and rising fascism. Additionally, Kahlo’s haunting work memorializing socialite Dorothy Hale’s 1938 suicide in New York is included in the exhibition. In 1933, “The University in Exile” was founded as part of the New School to provide employment for exiled European artists and intellectuals. As part of this, the school held a series of lectures and exhibitions entitled “European Surrealists in Exile” in 1941 and fostered an interest in the relationship between art and psychology through a rich range of courses.

The British master printmaker Stanley William Hayter relocated his famed Parisian print shop, Atelier 17, to The New School in 1940, where it served expatriate artists. Encouraging automatist practices, the print studio mingled American, European, Caribbean, and Latin American artists. These included Chilean Roberto Sebastian Antonio “Matta” Echaurren, who arrived in New York in 1939, and who later traveled with his Atelier 17 colleague, Robert Motherwell, to Mexico in 1941. Their intense and close connection will be featured in Nexus New York through Motherwell’s “Mexican Sketchbook” and several of Matta’s paintings from the period, including the 16-foot long Science, Conscience, Et Patience Du Vitreur.

Maria Martins Pereria e Souza of Brazil arrived in the country in 1940, and after an exhibition at the Corcoran Museum, Washington D.C., she traveled to New York in 1941, studying with Hayter and sculptor Jacques Lipschitz. Her broadly influential sculptures and jewelry were included in André Breton’s Surrealism and Painting as well as Marcel Jean’s later book, History of Surrealist Painting. Later, it would come to light that Martins had an affair with Marcel Duchamp, and served as his muse for Étant Donnés, which Duchamp worked on in secret from 1946 to 1966. Martin’s sculpture as well as images of Duchamp’s Etant Donnés manual will illuminate Martin’s influence on Duchamp.