El Museo del Barrio announced today that it is presenting TESTIMONIOS: 100 Years of Popular Expression in its galleries through May 6, 2012. The exhibition draws on rarely seen works by non-traditionally trained makers from El Museo del Barrio’s Permanent Collection and loans from the New York area. TESTIMONIOS bears witness to mankind’s artistic manifestations created under difficult circumstances or for spiritual or communal celebrations. This uplifting exhibition is organized by El Museo del Barrio and curated by Deborah Cullen, Director of Curatorial Programs at the museum.

Testimonios: 100 Years of Popular Expression will feature works and artist projects by well-known and beloved self-taught artists such as the Puerto Rican sculptor, Gregorio Marzán (1906-1997) and the Mexican draftsman, Martín Ramírez (1895-1963), both of whose intense visions allowed them to forge highly personal and intricate works.

Projects undertaken by professional artists working with broader creative communities will be featured as well. Photographer Ejlat Feuer’s (b. 1950) documentation of the beauty, diversity, and cultural significance of casitas, small structures built in community gardens located in New York’s Puerto Rican neighborhoods, will be among those featured.

The exhibition is comprised of a vast range of artistic expression and purpose, including a large selection of santos de palo (small, carved, polychromed wooden saints created for domestic altars) from the Spanish Caribbean, evincing both continuity and innovation within the humble devotional form. Among other works, a range of Vodun banners (ornately sequined textiles created for the Afro-Haitian religion) is notable as a study in both syncretism and design. Audiences will have the opportunity to explore the rich visual language of paño (handkerchief) drawings, painstakingly elaborated by Mexican-American inmates in Texas to communicate their histories and hopes to their loved ones. Finally, the unique textile idiom of the Kuna (Panama and Colombia), crafted in colorful, layered molas, depicts their worldview.

El Museo’s galleries are divided as follows:

Casitas & Santos: Ejlat Feuer photographed community gardens in El Barrio, the Lower East Side, and the South Bronx, where Puerto Ricans and other community groups draw upon Caribbean agricultural and architectural traditions to transform vacant lots into garden sites with ‘casitas,’ or small houses, for community exchange and celebration. Featured alongside Feuer’s work, are santos de palo, or “saints made of wood,” primarily from Puerto Rico, representing holy figures and traditions of popular Catholicism that were used to convert native populations and African slaves. Many were also traditionally placed in household altars.

Vodun Banners & Madama Dolls: Practitioners of Vodun (the African word for “spirit”) honor a pantheon of spirits resembling Christian saints, called Loa, who led exceptional lives and are associated with particular powers or attributes. This gallery will also feature Madama Dolls previously owned by Dr. Manual Aulí, whose specialty was emergency trauma. The dolls facilitated communication with patients from other cultures. In Espiritismo (Spiritism), la madama is a spiritual assistant who functions as a protector and who maintains the African traditions in the culture and conveys messages to those seeking guidance. Sacred objects are often sewn inside these dolls to protect its owner and their family.

Molas & Marzán Sculptures: Mola refers to the decorative, hand-made panels in the blouses worn by Kuna women, as well as the entire garment that contains them. Originating from the tradition of Kuna women painting their bodies with geometrical designs, motifs include plants, animals, images from Kuna mythology and biblical scenes after the arrival of missionaries in the early 20th century. Also highlighted are the works of Gregorio Marzán, a self-taught artist who created a fantastical sculptural menagerie. After emigrating from Puerto Rico to New York in 1937, Marzán worked in bomb manufacturing but later became a “doll stuffer” at factories around the city. Marzán turned to art after retirement at age sixty-five using materials picked up in the neighborhood discount shops. “Nobody taught me, I made from the brain,” he once commented.

Paños: Paños are standard cotton handkerchiefs that are transformed into expressive, emotional works of art by correctional facility inmates that are sent as letters to loved ones. Their creators were artists or others who worked in artistic fields prior to their incarceration, many returning to art after their release. Wardens began banning the practice in the 1990s when gang imagery appeared. Paños frequently convey love and longing for family as well as personal journeys in life from crime to redemption.

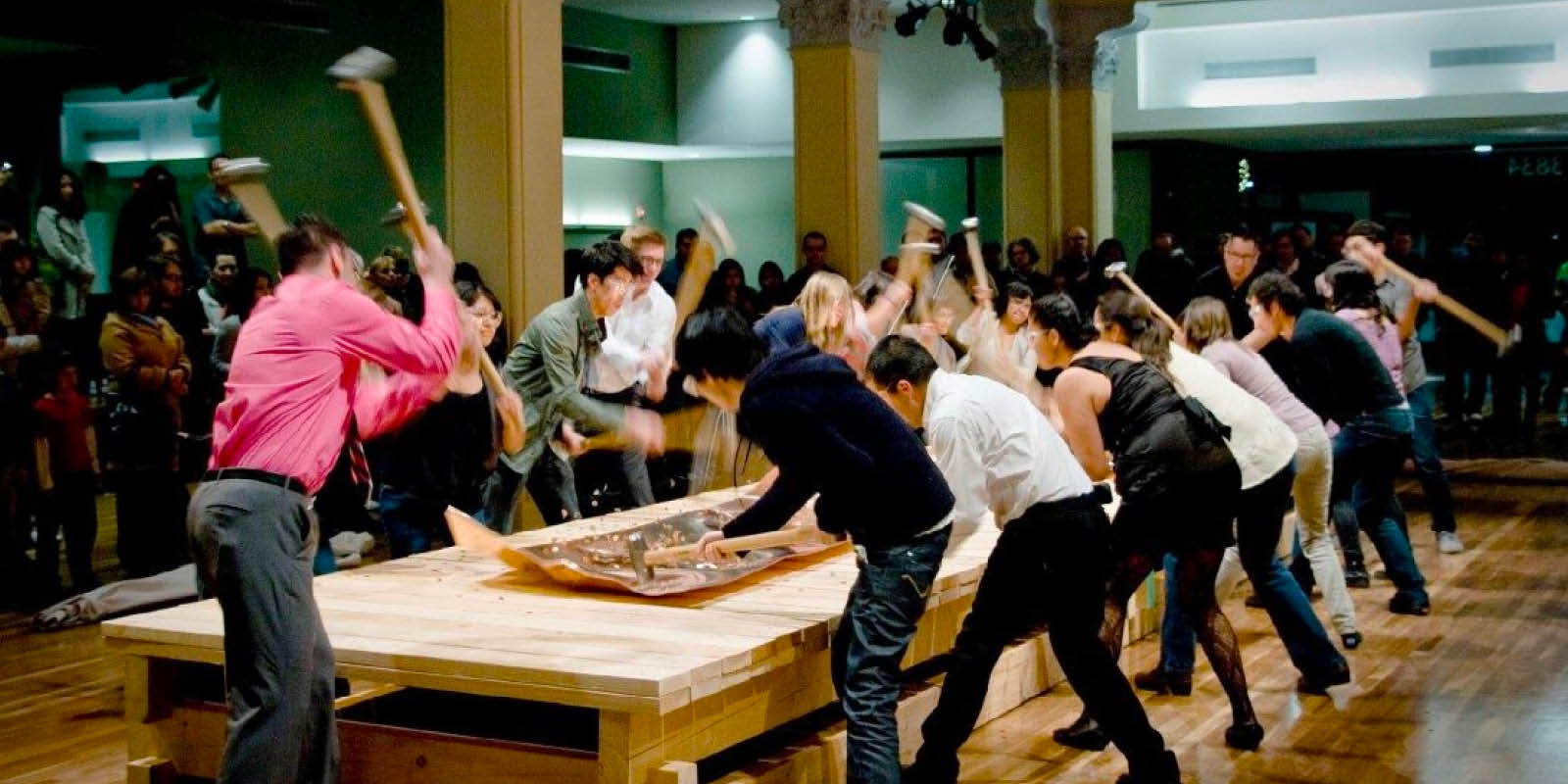

Arpilleras & Margarita Cabrera: In Chile, on September 11, 1973, the freely elected government of Salvador Allende Gossens was overthrown by a violent coup, enacted by a military junta headed by Augusto Pinochet. The arpillera is one of the most potent art forms that flourished during this dark time. Arpilleras are small wall- hangings made from scraps of cloth attached to burlap food-sack backings that portray life under military rule, the desolate experiences of exile, and the search for “the disappeared.” Each arpillera helped ease isolation and fear of its female maker, often including pieces of clothing from missing loved ones. This tradition ended when democracy arrived in Chile in 1990 under Patricio Alwyn. Margarita Cabrera’s (b. 1973) workshops with female immigrants from Mexico resulted in the evocative works on display, as these women shared their stories of crossing the border by embroidering narratives on cactuses crafted from used U.S. border patrol uniforms.